The AI revolution is underhyped

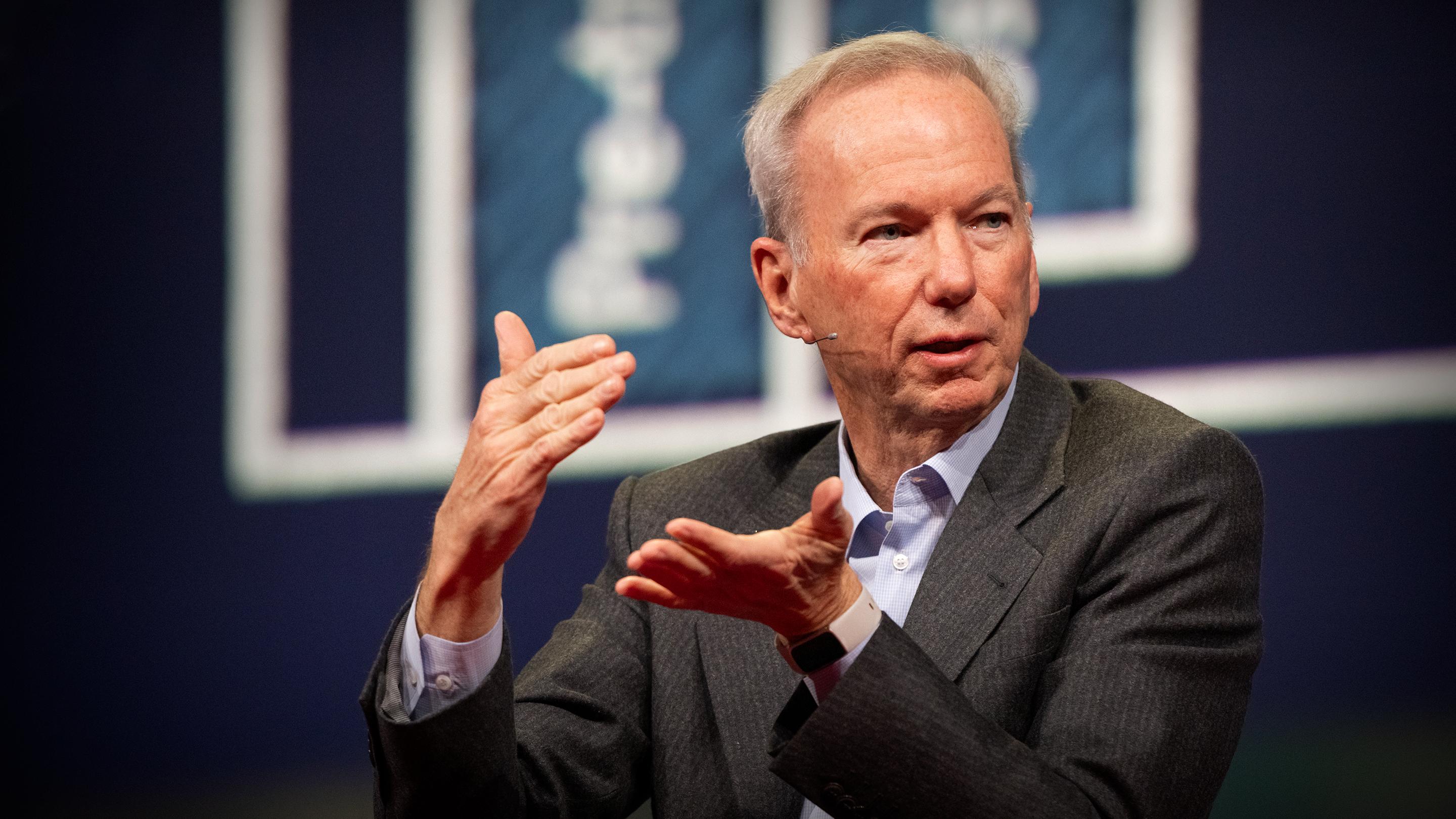

Bilawal Sidhu: Eric Schmidt, thank you for joining us.

Let's go back.

You said the arrival of non-human intelligence is a very big deal.

And this photo, taken in 2016,

feels like one of those quiet moments where the Earth shifted beneath us,

but not everyone noticed.

What did you see back then that the rest of us might have missed?

Eric Schmidt: In 2016, we didn't understand

what was now going to happen,

but we understood that these algorithms were new and powerful.

What happened in this particular set of games

was in roughly the second game,

there was a new move invented by AI

in a game that had been around for 2,500 years

that no one had ever seen.

Technically, the way this occurred

was that the system of AlphaGo was essentially organized

to always maintain a greater than 50 percent chance of winning.

And so it calculated correctly this move,

which was this great mystery among all of the Go players

who are obviously insanely brilliant,

mathematical and intuitive players.

The question that Henry, Craig Mundie and I started to discuss, right,

is what does this mean?

How is it that our computers could come up with something

that humans had never thought about?

I mean, this is a game played by billions of people.

And that began the process that led to two books.

And I think, frankly,

is the point at which the revolution really started.

BS: If you fast forward to today,

it seems that all anyone can talk about is AI,

especially here at TED.

But you've taken a contrarian stance.

You actually think AI is underhyped.

Why is that?

ES: And I'll tell you why.

Most of you think of AI as,

I'll just use the general term, as ChatGPT.

For most of you, ChatGPT was the moment where you said,

"Oh my God,

this thing writes, and it makes mistakes,

but it's so brilliantly verbal."

That was certainly my reaction.

Most people that I knew did that.

BS: It was visceral, yeah.

ES: This was two years ago.

Since then, the gains in what is called reinforcement learning,

which is what AlphaGo helped invent and so forth,

allow us to do planning.

And a good example is look at OpenAI o3

or DeepSeek R1,

and you can see how it goes forward and back,

forward and back, forward and back.

It's extraordinary.

In my case, I bought a rocket company

because it was like, interesting.

BS: (Laughs) As one does.

ES: As one does.

And it’s an area that I’m not an expert in,

and I want to be an expert.

So I'm using deep research.

And these systems are spending 15 minutes writing these deep papers.

That's true for most of them.

Do you have any idea how much computation

15 minutes of these supercomputers is?

It's extraordinary.

So you’re seeing the arrival,

the shift from language to language.

Tthen you had language to sequence,

which is how biology is done.

Now you're doing essentially planning and strategy.

The eventual state of this

is the computers running all business processes, right?

So you have an agent to do this, an agent to do this,

an agent to do this.

And you concatenate them together,

and they speak language among each other.

They typically speak English language.

BS: I mean, speaking of just the sheer compute requirements of these systems,

let's talk about scale briefly.

You know, I kind of think of these AI systems as Hungry Hungry Hippos.

They seemingly soak up all the data and compute that we throw at them.

They've already digested all the tokens on the public internet,

and it seems we can't build data centers fast enough.

What do you think the real limits are,

and how do we get ahead of them

before they start throttling AI progress?

ES: So there's a real limit in energy.

Give you an example.

There's one calculation,

and I testified on this this week in Congress,

that we need another 90 gigawatts of power in America.

My answer, by the way, is, think Canada, right?

Nice people, full of hydroelectric power.

But that's apparently not the political mood right now.

Sorry.

So 90 gigawatts is 90 nuclear power plants in America.

Not happening.

We're building zero, right?

How are we going to get all that power?

This is a major, major national issue.

You can use the Arab world,

which is busy building five to 10 gigawatts of data centers.

India is considering a 10-gigawatt data center.

To understand how big gigawatts are,

is think cities per data center.

That's how much power these things need.

And the people look at it and they say,

“Well, there’s lots of algorithmic improvements,

and you will need less power."

There's an old rule, I'm old enough to remember, right?

Grove giveth, Gates taketh away.

OK, the hardware just gets faster and faster.

The physicists are amazing.

Just incredible what they've been able to do.

And us software people, we just use it and use it and use it.

And when you look at planning, at least in today's algorithms,

it's back and forth and try this and that

and just watch it yourself.

There are estimates, and you know this from Andreessen Horowitz reports,

it's been well studied,

that there's an increase in at least a factor of 100,

maybe a factor of 1,000,

in computation required just to do the kind of planning.

The technology goes from essentially deep learning to reinforcement learning

to something called test-time compute,

where not only are you doing planning,

but you're also learning while you're doing planning.

That is the, if you will,

the zenith or what have you, of computation needs.

That's problem number one, electricity and hardware.

Problem number two is we ran out of data

so we have to start generating it.

But we can easily do that because that's one of the functions.

And then the third question that I don't understand

is what's the limit of knowledge?

I'll give you an example.

Let's imagine we are collectively all of the computers in the world,

and we're all thinking

and we're all thinking based on knowledge that exists that was previously invented.

How do we invent something completely new?

So, Einstein.

So when you study the way scientific discovery works,

biology, math, so forth and so on,

what typically happens is a truly brilliant human being

looks at one area and says,

"I see a pattern

that's in a completely different area,

has nothing to do with the first one.

It's the same pattern."

And they take the tools from one and they apply it to another.

Today, our systems cannot do that.

If we can get through that, I'm working on this,

a general technical term for this is non-stationarity of objectives.

The rules keep changing.

We will see if we can solve that problem.

If we can solve that, we're going to need even more data centers.

And we'll also be able to invent completely new schools of scientific

and intellectual thought,

which will be incredible.

BS: So as we push towards a zenith,

autonomy has been a big topic of discussion.

Yoshua Bengio gave a compelling talk earlier this week,

advocating that AI labs should halt the development of agentic AI systems

that are capable of taking autonomous action.

Yet that is precisely what the next frontier is for all these AI labs,

and seemingly for yourself, too.

What is the right decision here?

ES: So Yoshua is a brilliant inventor of much of what we're talking about

and a good personal friend.

And we’ve talked about this, and his concerns are very legitimate.

The question is not are his concerns right,

but what are the solutions?

So let's think about agents.

So for purposes of argument, everyone in the audience is an agent.

You have an input that's English or whatever language.

And you have an output that’s English, and you have memory,

which is true of all humans.

Now we're all busy working,

and all of a sudden, one of you decides

it's much more efficient not to use human language,

but we'll invent our own computer language.

Now you and I are sitting here, watching all of this,

and we're saying, like, what do we do now?

The correct answer is unplug you, right?

Because we're not going to know,

we're just not going to know what you're up to.

And you might actually be doing something really bad or really amazing.

We want to be able to watch.

So we need provenance, something you and I have talked about,

but we also need to be able to observe it.

To me, that's a core requirement.

There's a set of criteria that the industry believes are points

where you want to, metaphorically, unplug it.

One is where you get recursive self-improvement,

which you can't control.

Recursive self-improvement is where the computer is off learning,

and you don't know what it's learning.

That can obviously lead to bad outcomes.

Another one would be direct access to weapons.

Another one would be that the computer systems decide to exfiltrate themselves,

to reproduce themselves without our permission.

So there's a set of such things.

The problem with Yoshua's speech, with respect to such a brilliant person,

is stopping things in a globally competitive market

doesn't really work.

Instead of stopping agentic work,

we need to find a way to establish the guardrails,

which I know you agree with because we’ve talked about it.

(Applause)

BS: I think that brings us nicely to the dilemmas.

And let's just say there are a lot of them when it comes to this technology.

The first one I'd love to start with, Eric,

is the exceedingly dual-use nature of this tech, right?

It's applicable to both civilian and military applications.

So how do you broadly think about the dilemmas

and ethical quandaries

that come with this tech and how humans deploy them?

ES: In many cases, we already have doctrines

about personal responsibility.

A simple example, I did a lot of military work

and continue to do so.

The US military has a rule called 3000.09,

generally known as "human in the loop" or "meaningful human control."

You don't want systems that are not under our control.

It's a line we can't cross.

I think that's correct.

I think that the competition between the West,

and particularly the United States,

and China,

is going to be defining in this area.

And I'll give you some examples.

First, the current government has now put in

essentially reciprocating 145-percent tariffs.

That has huge implications for the supply chain.

We in our industry depend on packaging

and components from China that are boring, if you will,

but incredibly important.

The little packaging and the little glue things and so forth

that are part of the computers.

If China were to deny access to them, that would be a big deal.

We are trying to deny them access to the most advanced chips,

which they are super annoyed about.

Dr. Kissinger asked Craig and I

to do Track II dialogues with the Chinese,

and we’re in conversations with them.

What's the number one issue they raise?

This issue.

Indeed, if you look at DeepSeek, which is really impressive,

they managed to find algorithms that got around the problems

by making them more efficient.

Because China is doing everything open source, open weights,

we immediately got the benefit of their invention

and have adopted into US things.

So we're in a situation now which I think is quite tenuous,

where the US is largely driving, for many, many good reasons,

largely closed models, largely under very good control.

China is likely to be the leader in open source unless something changes.

And open source leads to very rapid proliferation around the world.

This proliferation is dangerous at the cyber level and the bio level.

But let me give you why it's also dangerous in a more significant way,

in a nuclear-threat way.

Dr. Kissinger, who we all worked with very closely,

was one of the architects of mutually assured destruction,

deterrence and so forth.

And what's happening now is you've got a situation

where -- I'll use an example.

It's easier if I explain.

You’re the good guy, and I’m the bad guy, OK?

You're six months ahead of me,

and we're both on the same path for superintelligence.

And you're going to get there, right?

And I'm sure you're going to get there, you're that close.

And I'm six months behind.

Pretty good, right?

Sounds pretty good.

No.

These are network-effect businesses.

And in network-effect businesses,

it is the slope of your improvement that determines everything.

So I'll use OpenAI or Gemini,

they have 1,000 programmers.

They're in the process of creating a million AI software programmers.

What does that do?

First, you don't have to feed them except electricity.

So that's good.

And they don't quit and things like that.

Second, the slope is like this.

Well, as we get closer to superintelligence,

the slope goes like this.

If you get there first, you dastardly person --

BS: You're never going to be able to catch me.

ES: I will not be able to catch you.

And I've given you the tools

to reinvent the world and in particular, destroy me.

That's how my brain, Mr. Evil, is going to think.

So what am I going to do?

The first thing I'm going to do is try to steal all your code.

And you've prevented that because you're good.

And you were good.

So you’re still good, at Google.

Second, then I'm going to infiltrate you with humans.

Well, you've got good protections against that.

You know, we don't have spies.

So what do I do?

I’m going to go in, and I’m going to change your model.

I'm going to modify it.

I'm going to actually screw you up

to get me so I'm one day ahead of you.

And you're so good, I can't do that.

What's my next choice?

Bomb your data center.

Now do you think I’m insane?

These conversations are occurring

around nuclear opponents today in our world.

There are legitimate people saying

the only solution to this problem is preemption.

Now I just told you that you, Mr. Good,

are about to have the keys to control the entire world,

both in terms of economic dominance,

innovation, surveillance,

whatever it is that you care about.

I have to prevent that.

We don't have any language in our society,

the foreign policy people have not thought about this,

and this is coming.

When is it coming?

Probably five years.

We have time.

We have time for this conversation.

And this is really important.

BS: Let me push on this a little bit.

So if this is true

and we can end up in this sort of standoff scenario

and the equivalent of mutually-assured destruction,

you've also said that the US should embrace open-source AI

even after China's DeepSeek showed what's possible

with a fraction of the compute.

But doesn't open-sourcing these models,

just hand capabilities to adversaries that will accelerate their own timelines?

ES: This is one of the wickedest, or, we call them wicked hard problems.

Our industry, our science,

everything about the world that we have built

is based on academic research, open source, so forth.

Much of Google's technology was based on open source.

Some of Google's technology is open-source,

some of it is proprietary, perfectly legitimate.

What happens when there's an open-source model

that is really dangerous,

and it gets into the hands of the Osama bin Ladens of the world,

and we know there are more than one, unfortunately.

We don't know.

The consensus in the industry right now

is the open-source models are not quite at the point

of national or global danger.

But you can see a pattern where they might get there.

So a lot will now depend upon the key decisions made in the US and China

and in the companies in both places.

The reason I focus on US and China

is they're the only two countries where people are crazy enough

to spend the billions and billions of dollars

that are required to build this new vision.

Europe, which would love to do it,

doesn't have the capital structure to do it.

Most of the other countries, not even India,

has the capital structure to do it, although they wish to.

Arabs don't have the capital structure to do it,

although they're working on it.

So this fight, this battle, will be the defining battle.

I'm worried about this fight.

Dr. Kissinger talked about the likely path to war with China

was by accident.

And he was a student of World War I.

And of course, [it] started with a small event,

and it escalated over that summer in, I think, 1914.

And then it was this horrific conflagration.

You can imagine a series of steps

along the lines of what I'm talking about

that could lead us to a horrific global outcome.

That's why we have to be paying attention.

BS: I want to talk about one of the recurring tensions here,

before we move on to the dreams,

is, to sort of moderate these AI systems at scale, right,

there's this weird tension in AI safety

that the solution to preventing "1984"

often sounds a lot like "1984."

So proof of personhood is a hot topic.

Moderating these systems at scale is a hot topic.

How do you view that trade-off?

In trying to prevent dystopia,

let's say preventing non-state actors

from using these models in undesirable ways,

we might accidentally end up building the ultimate surveillance state.

ES: It's really important that we stick to the values

that we have in our society.

I am very, very committed to individual freedom.

It's very easy for a well-intentioned engineer to build a system

which is optimized and restricts your freedom.

So it's very important that human freedom be preserved in this.

A lot of these are not technical issues.

They're really business decisions.

It's certainly possible to build a surveillance state,

but it's also possible to build one that's freeing.

The conundrum that you're describing

is because it's now so easy to operate based on misinformation,

everyone knows what I'm talking about,

that you really do need proof of identity.

But proof of identity does not have to include details.

So, for example, you could have a cryptographic proof

that you are a human being,

and it could actually be true without anything else,

and also not be able to link it to others

using various cryptographic techniques.

BS: So zero-knowledge proofs and other techniques.

ES: Zero-knowledge proofs are the most obvious one.

BS: Alright, let's change gears, shall we, to dreams.

In your book, "Genesis," you strike a cautiously optimistic tone,

which you obviously co-authored with Henry Kissinger.

When you look ahead to the future, what should we all be excited about?

ES: Well, I'm of the age

where some of my friends are getting really dread diseases.

Can we fix that now?

Can we just eliminate all of those?

Why can't we just uptake these

and right now, eradicate all of these diseases?

That's a pretty good goal.

I'm aware of one nonprofit that's trying to identify,

in the next two years,

all human druggable targets and release it to the scientists.

If you know the druggable targets,

then the drug industry can begin to work on things.

I have another company I'm associated with

which has figured out a way, allegedly, it's a startup,

to reduce the cost of stage-3 trials by an order of magnitude.

As you know, those are the things

that ultimately drive the cost structure of drugs.

That's an example.

I'd like to know where dark energy is,

and I'd like to find it.

I'm sure that there is an enormous amount of physics in dark energy, dark matter.

Think about the revolution in material science.

Infinitely more powerful transportation,

infinitely more powerful science and so forth.

I'll give you another example.

Why do we not have every human being on the planet

have their own tutor in their own language

to help them learn something new?

Starting with kindergarten.

It's obvious.

Why have we not built it?

The answer, the only possible answer

is there must not be a good economic argument.

The technology works.

Teach them in their language, gamify the learning,

bring people to their best natural lengths.

Another example.

The vast majority of health care in the world

is either absent

or delivered by the equivalent of nurse practitioners

and very, very sort of stressed local village doctors.

Why do they not have the doctor assistant that helps them in their language,

treat whatever with, again, perfect healthcare?

I can just go on.

There are lots and lots of issues with the digital world.

It feels like that we're all in our own ships in the ocean,

and we're not talking to each other.

In our hunger for connectivity and connection,

these tools make us lonelier.

We've got to fix that, right?

But these are fixable problems.

They don't require new physics.

They don't require new discoveries, we just have to decide.

So when I look at this future,

I want to be clear that the arrival of this intelligence,

both at the AI level, the AGI,

which is general intelligence,

and then superintelligence,

is the most important thing that's going to happen in about 500 years,

maybe 1,000 years in human society.

And it's happening in our lifetime.

So don't screw it up.

BS: Let's say we don't.

(Applause)

Let's say we don't screw it up.

Let's say we get into this world of radical abundance.

Let's say we end up in this place,

and we hit that point of recursive self-improvement.

AI systems take on a vast majority of economically productive tasks.

In your mind, what are humans going to do in this future?

Are we all sipping piña coladas on the beach, engaging in hobbies?

ES: You tech liberal, you.

You must be in favor of UBI.

BS: No, no, no.

ES: Look, humans are unchanged

in the midst of this incredible discovery.

Do you really think that we're going to get rid of lawyers?

No, they're just going to have more sophisticated lawsuits.

Do you really think we're going to get rid of politicians?

No, they'll just have more platforms to mislead you.

Sorry.

I mean, I can just go on and on and on.

The key thing to understand about this new economics

is that we collectively, as a society, are not having enough humans.

Look at the reproduction rate in Asia,

is essentially 1.0 for two parents.

This is not good, right?

So for the rest of our lives,

the key problem is going to get the people who are productive.

That is, in their productive period of lives,

more productive to support old people like me, right,

who will be bitching that we want more stuff from the younger people.

That's how it's going to work.

These tools will radically increase that productivity.

There's a study that says that we will,

under this set of assumptions around agentic AI and discovery

and the scale that I'm describing,

there's a lot of assumptions

that you'll end up

with something like 30-percent increase in productivity per year.

Having now talked to a bunch of economists,

they have no models

for what that kind of increase in productivity looks like.

We just have never seen it.

It didn't occur in any rise of a democracy or a kingdom in our history.

It's unbelievable what's going to happen.

Hopefully we will get it in the right direction.

BS: It is truly unbelievable.

Let's bring this home, Eric.

You've navigated decades of technological change.

For everyone that's navigating this AI transition,

technologists, leaders, citizens

that are feeling a mix of excitement and anxiety,

what is that single piece of wisdom

or advice you'd like to offer

for navigating this insane moment that we're living through today?

ES: So one thing to remember

is that this is a marathon, not a sprint.

One year I decided to do a 100-mile bike race,

which was a mistake.

And the idea was, I learned about spin rate.

Every day, you get up, and you just keep going.

You know, from our work together at Google,

that when you’re growing at the rate that we’re growing,

you get so much done in a year,

you forget how far you went.

Humans can't understand that.

And we're in this situation

where the exponential is moving like this.

As this stuff happens quicker,

you will forget what was true two years ago or three years ago.

That's the key thing.

So my advice to you all is ride the wave, but ride it every day.

Don't view it as episodic and something you can end,

but understand it and build on it.

Each and every one of you has a reason to use this technology.

If you're an artist, a teacher, a physician,

a business person, a technical person.

If you're not using this technology,

you're not going to be relevant compared to your peer groups

and your competitors

and the people who want to be successful.

Adopt it, and adopt it fast.

I have been shocked at how fast these systems --

as an aside, my background is enterprise software,

and nowadays there's a model Protocol from Anthropic.

You can actually connect the model directly into the databases

without any of the connectors.

I know this sounds nerdy.

There's a whole industry there that goes away

because you have all this flexibility now.

You can just say what you want, and it just produces it.

That's an example of a real change in business.

There are so many of these things coming every day.

BS: Ladies and gentlemen, Eric Schmidt.

ES: Thank you very much.

AITransDub

AI varomas vaizdo įrašų vertimas ir dubliavimas

Akimirksniu sulaužykite kalbos kliūtis! AI varomas tikslus vertimas ir greitas jūsų vaizdo įrašų dubliavimas.